Ancient Egyptian Money: The Fascinating History of Currency in the Land of Pharaohs

When we think of ancient Egypt, images of towering pyramids, golden sarcophagi, and powerful pharaohs come to mind. But have you ever wondered how ancient Egyptians paid for goods and services? The story of ancient Egyptian money is more complex and fascinating than you might expect, revealing a civilization that operated for millennia without what we'd recognize as traditional currency.

Did Ancient Egypt Have Money?

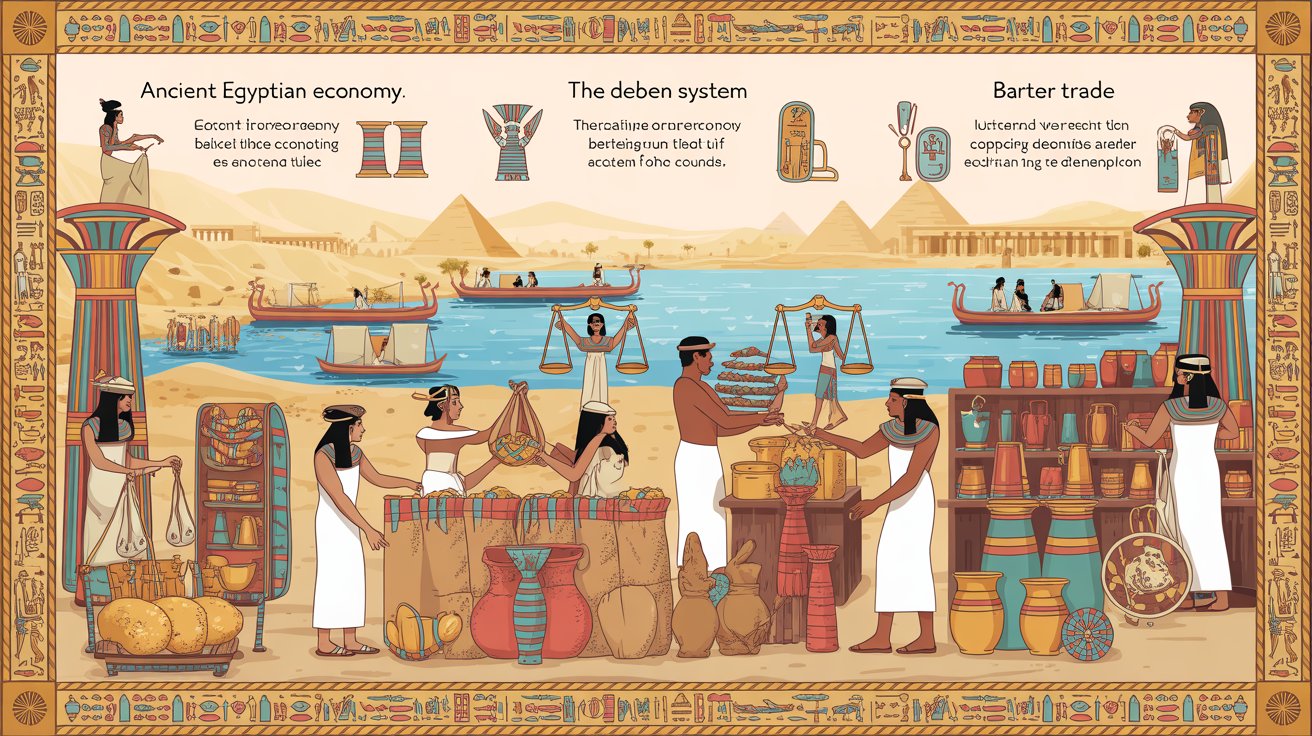

The short answer is: not in the way we think of money today. For most of ancient Egyptian history—spanning over 3,000 years—the civilization functioned primarily on a barter economy. Instead of coins or paper bills, Egyptians exchanged goods and services directly with one another.

However, this doesn't mean their economic system was primitive. Ancient Egypt developed sophisticated methods of valuing and exchanging goods that laid groundwork for future monetary systems.

The Deben: Ancient Egypt's Unit of Account

While ancient Egyptians didn't use physical coins for most of their history, they did have a standard unit for measuring value: the deben.

What Was a Deben?

The deben was a weight measurement, originally equivalent to about 91 grams (later reduced to about 91 grams of copper). It served as an abstract unit of account—similar to how we use dollars or euros today—but without physical coins representing it.

Think of the deben as an accounting tool. When Egyptians wanted to trade, they would calculate the value of their goods in debens, then exchange items of equivalent value. For example:

- 1 goat might equal 1 deben

- A pair of sandals might equal 2 debens

- A fine linen shirt could be worth 5 debens

The Shat: Smaller Denominations

For smaller transactions, the ancient Egyptians used the shat, which was 1/12 of a deben. This allowed for more precise valuations in everyday trade.

What Did Ancient Egyptians Use as Currency?

Before coins arrived in Egypt, several commodities served as common mediums of exchange:

1. Grain and Bread

Grain, particularly emmer wheat and barley, was one of the most important commodities in ancient Egypt. It was:

- Easy to store (when kept dry)

- Essential for survival

- Used to pay workers' wages

- The basis for calculating other values

Workers building the pyramids and temples often received their wages in grain rations, along with beer, which was considered a staple food rather than just a beverage.

2. Copper and Bronze

Metal, especially copper and later bronze, became increasingly important as a medium of exchange. Copper was valuable because it could be:

- Melted down and reformed

- Used to make tools and weapons

- Stored compactly

- Divided into smaller pieces

Copper rings, sometimes called "utenu," became a common form of proto-currency in the New Kingdom period.

3. Gold and Silver

Precious metals held significant value in ancient Egypt:

- Gold was abundant in Nubia (southern Egypt and Sudan) and highly prized

- Silver was actually rarer than gold in Egypt and sometimes valued more highly

- Both were weighed carefully for high-value transactions

- They were used primarily for trade with foreign nations and for temple offerings

4. Livestock

Animals, particularly cattle, goats, and sheep, served as valuable trade commodities:

- They could be bred to increase wealth

- They provided milk, meat, and labor

- Their value was well understood across society

- They were portable (literally walking) wealth

When Did Ancient Egypt Start Using Coins?

True coinage didn't arrive in Egypt until relatively late in its history.

The Persian Period (525-404 BCE)

Egypt first encountered coins during the Persian conquest. Persian darics—gold coins featuring a kneeling archer—circulated among merchants and administrators, but they didn't immediately replace the traditional barter system among everyday Egyptians.

The Ptolemaic Period (305-30 BCE)

After Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, his successors—the Ptolemaic dynasty—introduced a Greek-style monetary system to Egypt. The Ptolemies minted their own coins, including:

- Gold coins (often featuring rulers' portraits)

- Silver tetradrachms (four-drachma pieces)

- Bronze coins for everyday transactions

This period marked the true beginning of a coin-based economy in Egypt, though it came nearly 3,000 years after the rise of ancient Egyptian civilization.

How Did Ancient Egyptian Markets Work?

The ancient Egyptian marketplace operated on negotiation and equivalence. Here's how a typical transaction might unfold:

- Assessment: A buyer would approach a seller with goods to trade

- Valuation: Both parties would calculate the deben value of their goods

- Negotiation: They would haggle over the fair exchange rate

- Exchange: Once agreed, goods changed hands

- Record-keeping: Scribes might record larger transactions

The Role of Scribes

Scribes were essential to Egypt's economy. They:

- Recorded transactions and tax payments

- Calculated values in debens and shats

- Maintained inventory for temples and government

- Documented workers' wages

Taxes in Ancient Egypt: Paying the Pharaoh

Taxes weren't paid in money but in goods and labor:

- Farmers paid taxes with a portion of their harvest

- Craftsmen gave a percentage of their production

- Workers owed labor service (corvée) to the state

- Fishermen paid in fish

Tax collectors, often depicted in tomb paintings, would visit villages to assess and collect these payments. The pharaoh's administration redistributed these collected goods to pay government workers, fund building projects, and support temples.

The Worker's Village at Deir el-Medina: A Case Study

One of our best sources for understanding ancient Egyptian economics comes from Deir el-Medina, the village of workers who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

Archaeological evidence shows that these skilled workers:

- Received monthly grain rations as wages

- Traded goods and services among themselves

- Recorded debts in written documents (ostraca)

- Sometimes went on strike when payments were delayed—one of history's first recorded labor strikes!

These records reveal a complex economy with credit, debt, and intricate exchange networks—all without coins.

Ancient Egyptian "Banks": Temples and Granaries

While ancient Egypt didn't have banks in the modern sense, temples and royal granaries served similar functions:

- Storage facilities: They safeguarded grain and valuables

- Redistribution centers: They issued rations and payments

- Lending institutions: They could advance grain to farmers before harvest

- Record-keeping: Scribes maintained detailed accounts

The largest temples were economic powerhouses, owning vast estates, employing thousands, and accumulating enormous wealth.

International Trade: Egypt's External Economy

Egypt's position as a crossroads between Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean made it a trading hub:

What Egypt Exported:

- Grain (Egypt was the "breadbasket" of the ancient world)

- Gold from Nubian mines

- Papyrus (the ancient world's paper)

- Linen textiles

- Stone vessels and jewelry

What Egypt Imported:

- Cedar wood from Lebanon (Egypt had few trees)

- Silver from Anatolia and Greece

- Copper from Cyprus

- Incense and myrrh from Punt (modern-day Somalia/Eritrea)

- Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan

These international exchanges often involved high-value goods traded by weight in gold or silver, calculated in debens.

The Social Hierarchy and Wealth

Ancient Egyptian society was stratified, and wealth distribution reflected this:

- Pharaoh: Owned all land theoretically; controlled vast resources

- Nobles and priests: Received land grants and temple income

- Scribes and officials: Earned regular rations and gifts

- Craftsmen and merchants: Traded goods and services

- Farmers: Worked land and paid taxes to landowners

- Laborers: Received basic rations for work

Despite this hierarchy, evidence suggests that even ordinary Egyptians could accumulate wealth through trade and craftsmanship.

Why Did Ancient Egypt Function Without Coins?

The ancient Egyptian economy thrived without traditional currency for several reasons:

- Agricultural abundance: The Nile's reliable flooding created surplus food

- Central administration: Strong government facilitated redistribution

- Limited urbanism: Most people lived in villages where barter worked well

- Traditional stability: Systems that worked for centuries resisted change

- Adequate alternatives: The deben system and commodity money served their needs

Legacy: How Ancient Egypt Influenced Modern Money

While ancient Egypt didn't invent coinage, its economic innovations influenced later civilizations:

- Standardized weights: The concept of the deben influenced later systems

- Record-keeping: Egyptian accounting methods spread throughout the ancient world

- Precious metal valuation: Their methods of weighing gold and silver became standard practice

- Complex trade networks: They established routes and practices used for millennia

Conclusion: Understanding Ancient Egyptian Money

The story of ancient Egyptian money reveals a sophisticated economy that functioned successfully for thousands of years without coins. Through the deben accounting system, commodity exchanges, and centralized redistribution, ancient Egyptians created an economic framework that supported one of history's greatest civilizations.

Their system reminds us that "money" is ultimately about trust, standardization, and shared understanding of value—principles that remain at the heart of modern economics. Whether using grain, copper rings, or digital currencies, humans have always found ways to facilitate trade and build complex societies.

The next time you use coins or digital payments, remember that you're participating in an economic evolution that ancient Egyptians helped shape, even if they never dropped a coin in their own markets.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ancient Egyptian Money

Q: When did Egypt start using coins? A: Egypt began using coins during the Persian period (around 525 BCE) but didn't fully adopt a coin-based economy until the Ptolemaic period (after 305 BCE).

Q: What was a deben worth? A: A deben was a unit of weight (about 91 grams) used for valuation. Its purchasing power varied over time, but it might equal a goat or several days' grain rations.

Q: How were pyramid builders paid? A: Pyramid builders received wages in grain, beer, bread, and other necessities. They weren't slaves but paid workers, and records show they sometimes struck when payments were late.

Q: Did ancient Egyptians have rich and poor people? A: Yes, ancient Egypt had significant wealth inequality, with pharaohs and nobles controlling most resources while farmers and laborers worked for rations. However, skilled craftsmen could achieve comfortable middle-class status.

Q: What was the most valuable commodity in ancient Egypt? A: Gold was extremely valuable, but grain was arguably more important as it was essential for survival and used to pay most wages.